OIML BULLETIN - VOLUME LXV - NUMBER 3 - JULY 2024

e v o l u t i o n s

Weights and measures implementation framework for verified gross mass (VGM) guidelines under the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS)

Henry Maeda

Tanzania Weights and Measures Agency

(TWMA)

1 Introduction

At its 93rd session, held from 14 to 23 May 2014, the International Maritime Organization (IMO) Maritime Safety Committee (MSC) proposed a guideline regarding the Verified Gross Mass (VGM) of a container carrying cargo. The guideline intended to establish a common approach for the implementation and enforcement of the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) requirements regarding the verification of gross mass of the packed container (Djadjev & Djadjev, 2017; IMO, 2014).

In early 2015, this subject was brought to the attention of the International Bureau of Legal Metrology (BIML) by a message from the New Zealand Trading Standards Bureau. They had been asked to help implement these new regulations from the IMO which would make it compulsory to weigh freight containers before they are loaded onto ships.

1.1 Background to the study

1.1.1 International Maritime Organization SOLAS Convention

The IMO drew up the guideline, under SOLAS, which ensures ships’ safety for both workers aboard the ship and ashore, and for overall safety at sea. The 2016 amendments to Chapter VI, Part A, Regulatory 2 required shippers to submit the verified gross mass of a container carrying cargo (IMO, 2014) before that container is loaded onto a ship. Prior to the SOLAS amendment in 2016 the weight of the containers was declared by the shippers, and the process was found to be highly inaccurate.

1.1.2 Weights and Measures Agency awareness of the SOLAS guidelines

The Weights and Measures Agency (WMA) became aware of these IMO regulations through the agenda of the 50th CIML Meeting. One of the Additional Meeting Documents (50 CIML-AMD-11) “Legal metrology implication of an amendment to the International Maritime Organization”' emphasised the need for Member States to implement the new SOLAS requirements by 1 July 2016.

1.1.3 Scope of the Weights and Measures Agency

The WMA was formed under the executive agency Act of 1997, No. 30. The Agency operates under the Ministry of Industry and Trade with sole responsibility for protecting consumers in the areas of trade, safety, health and the environment in matters related to legal metrology. The work is done through approving, testing, inspection, calibration and certification (ATICC).

The WMA acts on behalf of the Government of Tanzania, and functions under the Weights and Measures Act Cap 340. It also utilises OIML Recommendations, Documents and Guides, since Tanzania is an OIML Member State.

1.1.4 Study objectives

- To define the implementation procedures for VGM guidelines under the Weights and Measures Act Cap 340.

- To identify the international legal metrology requirements regarding SOLAS requirements.

- To assess shippers’ obligations toward the SOLAS requirements under the Weights and Measures Act Cap 340.

- To describe procedures regarding SOLAS requirements under the Weights and Measures Act Cap 340.

1.2 Problem statement

Misdeclaration of container cargo mass has been a significant problem and has led to many incidents of collapsing container stacks, damaged containers, overturned vehicles and equipment, and even whole vessels capsizing (Capt. Richard Brough O.B.E & ICHCA, 2016; Devos, 2013). However, the IMO decided to adopt an amendment to the SOLAS Convention (Chapter VI, Part A, Regulatory 2) that requires the container’s gross mass to be verified prior to stowage on board a ship (Guevara & Dalaklis, 2021; IMO, 2016; Krilić, 2015; Rahmatika, Putri, Sirait, & Setyawati, 2017; Sánchez, 2016; Tai, 2016). Hence the verifying of container weight is rendered mandatory by the SOLAS 2016 amendment which provided for member states to govern requirements according to the country’s statutory laws.

2 Literature review

2.1 Global incidents on container overload

2.1.1 World Shipping Council (WSC) Report on Container Loss

When reviewing the results of the 14-year period (2008-2021) under consideration, the WSC estimated that on average, 1 629 containers were lost at sea each year, which is a significant increase (18 %) in the average annual loss for the 12-year period ending in 2019 (Hartog & Ninla Elmawati Falabiba, 2023). A study by (Rahim, 2019) shows incorrect stowage plans, overloading, and incorrect container stacking all contribute to ship accidents.

2.1.2 Lloyd Register report on misdeclaration

For over 260 years, Lloyd’s Register has been a leading provider of classification and compliance services to the marine and offshore industries. A report by the agency on container ship accidents during the first half of 2011 showed that mis-declared cargo is the third contributing factor causing ship accidents after leakages and explosions (Cristian, 2011).

2.1.3 Global economic impact on mis-declared containers

There are significant economic consequences associated with mis-declared container weights. According to the interim report on large container ship safety in response to the loss of MV MOL Comfort, (MSC 93/INF.14 (Bahamas and Japan) (2014), p 39), the insurance bill for the MSC Napoli was in the region of millions of USD. The Allianz Global Corporate & Specialty, Global Claims Review 2014, (September 2014), p 17 stated that the sinking of the MOL Comfort, which has also been associated with mis-declared container weights, was expected to cost insurers US$523 million.

2.1.4 The case of the Australia Senate testimony

In late 2008, the Australian Senate heard testimony from Customs and other officials that “approximately 80 % of consignments from developing countries are miss-declared” and that “the evasion of duty through undeclared cargo is considered to be another incentive for more container inspections.” (Cristian, 2011).

2.1.5 MSC Napoli accident

This incident happened in January 2007 when the ship lost a number of containers after mooring. The accident involved excess weights of containers which capsized the ship (Youssef & Aly, 2020).

2.1.6 MV Lamari accident

Records show that the collapse of the MV Limari was due to overloading of the containers and incorrect staffing (Svilen, 2013).

2.1.7 Global factors on ship accidents

A study (Rahim, 2019) conducted by Rahim concluded that there are four categories of factors which cause ship accidents: management of cargo logistics, the ship’s system, the environment, and human factors. Wasalaski, 2021, described the reasons for container loss; this was also explained by Rahim, 2019 as stacking and overloading contributes to ship accidents by reducing stability of the ship.

2.2 Local incidents of cargo overload accidents

Issues related to the overloading of ships and ferries in Tanzania is not a new aspect. In the tragedy of MV Bukoba in October 1996, which caused the ship to sink, one of the reasons was given as overloading (Fumbuka, 1999).

MV Nyerere capsized on 20 September 2008 and it was found that the overloading of passengers and cargo were largely responsible for the disaster. These situations cause ships to lose their stability (Goldstein, 2018).

2.3 Regulatory requirements

The Tanzania Shipping Agencies Corporation (TASAC) was established under the Tanzania Shipping Agencies Act Cap 415 to regulate the Maritime Transport Industry in mainland Tanzania. It provides the role of maritime administration, regulates the maritime sector, and facilitates shipping business including carrying out shipping agency business.

2.3.1 Tanzania Merchant Shipping Regulations 2016

In 2016, the Surface and Marine Transport Regulatory Authority (SUMATRA) (currently the Tanzania Shipping Corporation Agency (TASAC)) created a regulation which aligned with the IMO SOLAS Convention, Chapter VI, Part A, Regulation 2. This led to the creation of the Merchant Shipping (verified gross mass for container carrying cargo) Regulations 2016. Adopting the amended SOLAS Chapter VI, Regulation 2, the regulations commended the use of methods 1 and 2 in the process of verifying the container carrying cargo described in IMO MSC.1/Circ.1475, Guidelines Regarding the Verified Gross Mass of a container carrying cargo.

2.4 New Zealand experience on SOLAS requirements

The New Zealand Weights and Measures Bureau (the New Zealand Trading Standards Office) was asked to implement this new IMO regulation making it compulsory to weigh freight containers before they are loaded onto the ship. Using New Zealand’s Weights and Measures System SOLAS (King, 2016), the organisation was the pioneer concerning the implementation of the regulation (maritimenz.govt.nz/media/5ujjpn3k/using-nz-weights-measures-solas.pdf).

3 Methodology and approach

In this section, this study explains the SOLAS guidelines on Weights and Measures systems regarding the amendment of IMO MSC.1/Circ.1475, requirements.

3.1 Weights and Measures Systems in the SOLAS requirement

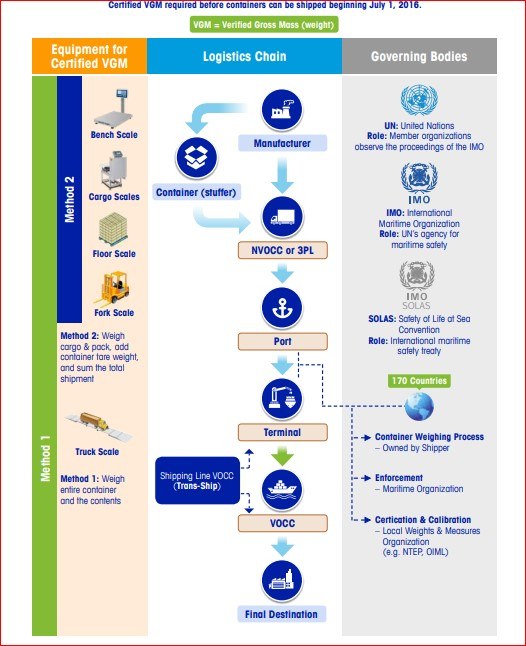

Through “IMO MSC.1/Circ.1475, Guidelines Regarding the Verified Gross Mass of a container carrying cargo”, the SOLAS framework for VGM has been structured according to the amendment of Chapter VI, Part A, Regulatory 2 of the SOLAS guideline. Hence the application can be assessed through this common information in the guidelines. Figure 1 shows a pictorial description of the SOLAS working framework (the infographic is courtesy of Mettler-Toledo International, Inc).

The description of the framework of the SOLAS guidelines for verified gross mass comprises three categories:

- Equipment for certified VGM;

- Logistics chain;

- Governing bodies.

Figure 1: SOLAS Guidelines

3.2 SOLAS methods

Under the IMO MSC.1/Circ.1475 guidelines regarding the verified gross mass of a container carrying cargo of June 2014, the methodology of processing the verified gross mass has been the subject of two methods, as described below.

3.2.1 SOLAS guidelines Method 1

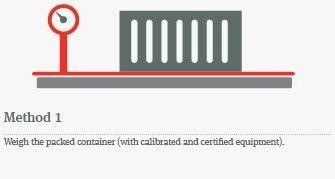

The SOLAS guidelines describes Method 1 as follows:

“Upon the conclusion of packing and sealing a container, the shipper may weigh, or have arranged that a third party weighs, the packed container”. (IMO, 2014).

In the merchant shipping regulation, Method 1 also states:

“gross mass verification involves weighing and determining the gross mass of the whole packed container after packing and sealing the container”(The Merchant Shipping, 2016).

Figure 2 shows a pictorial description of Method 1 (picture courtesy of Norton Rose Fulbright).

Figure 2: Method 1 Weigh the packed container

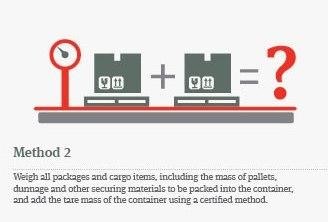

3.2.2 SOLAS Guidelines Method 2

The SOLAS guidelines describes Method 2 as follows in paragraphs 5.1.2.3 and 5.1.2.3.1

“The shipper (or, by arrangement of the shipper, a third party), may weigh all packages and cargo items, including the mass of pallets, dunnage and other packing and securing material to be packed in the container, and add the tare mass of the container to the sum of the single masses using a certified method.

Any third party that has performed some or all of the packing of the container should inform the shipper of the mass of the cargo items and packing and securing material that the party has packed into the container in order to facilitate the shipper's verification of the gross mass of the packed container under Method No.2. As required by SOLAS VI/2 and paragraph 5, the shipper should ensure that the verified gross mass of the container is provided sufficiently in advance of vessel loading. How such information is to be communicated between the shipper and any third party should be agreed between the commercial parties involved (IMO, 2014).”

Figure 3 shows a pictorial description of Method 2 (picture courtesy of Norton Rose Fulbright).

Figure 3: Weigh all packages and cargo items

The merchant shipping regulation for Method 2 states:

“Gross mass verification involves determining gross mass of packed container by weighing all individual packages and cargo items, including the mass of pallets, dunnage and other packing and securing material to be packed in the container and add the tare mass of the container to the sum of the single masses using a certified process” (The Merchant Shipping, 2016).

4 Discussion and application

4.1 Weights and Measures Agency requisite

The Weights and Measures Agency acts as an enforcement agency in all matters of legal metrology and mandates that services of measuring weights shall be of the accuracy stipulated by the Weights and Measures Act Cap 340, section 11:

- Weights and measures permitted to be used in trade

(1) Unless otherwise permitted by this Act, every contract, bargain, sale or dealing made or had after the commencement of this Act whereby any work, goods, wares, merchandise or other thing is or are to be, or is or are done, sold, delivered, carried, measured, computed, paid for or agreed for by weight or measure shall be made and had according to one of the relevant units of measurement specified in the First, Second, Third, Fourth, Sixth, Seventh and Eighth Schedules to this Act or to some multiple thereof, and if not so made or had, shall, so far as it is to be performed in the United Republic, be void:

Note:

“Furthermore, the SOLAS guideline 15.1 provides that any other incidence of non-compliance with the SOLAS requirements is enforceable according to national legislation”.

4.2 Weights and Measures Agency implementation

Referencing the amended (SOLAS) Chapter VI, Regulation 2, 5(1)(2)(3)(1), the state should abide either by the procedures for the weighing or by the party performing the weighing, or both. This implies that the state legislation and procedure should follow the SOLAS guidelines.

For instance, the Weights and Measures Act 340, section 49 describes:

“A document purporting to be signed by an assizer and certifying that a weighing or measuring instrument specified therein was inspected or examined and compared with the standard by him on a specified date and the finding of his examination or inspection shall be received in any court on production by any person and without further proof as prima faci evidence of the facts therein stated”.

This section allows the Agency to execute its legislative power which is defined in SOLAS Guideline 6.1 “Documentation”.

“The SOLAS regulations require the shipper to verify the gross mass of the packed container using Method No.1 or Method No.2 and to communicate the verified gross mass in a shipping document. This document can be part of the shipping instructions to the shipping company or a separate communication (e.g. a declaration including a weight certificate produced by a weigh station utilizing calibrated and certified equipment on the route between the shipper's origin and the port terminal). In either case, the document should clearly highlight that the gross mass provided is the “verified gross mass”.

5 Conclusion

This section underlines the importance of the role which is supposed to be played by the Weights and Measures Agency regarding the approach specified in SOLAS Guideline 5.1.2.3.1, Guideline 6 and Guideline 15.1, to mention the few with the national legislations, namely the Weights and Measures Act, section 11(1) (3) and section 49.

5.1 Summary

The Weights and Measures Agency is mandated to protect consumers and society against the consequences of incorrect measurements in both public and private transactions. Hence, the conclusion to this report provides the recommendations listed below that may be put into place.

5.2 Recommendations

- The Weights and Measures Agency has to execute its role by following the Weights and Measures Act Cap 340.

- The Weights and Measures Agency, through the industry regulator, must notify shippers to collaborate regarding SOLAS guidelines and the Weights and Measures Act Cap 340.

- Fully examine and approve VGM prior to submission to other processes of the SOLAS requirement and also the Weights and Measures Act 340, section 49.

6 Bibliography

- 50th CIML Meeting (2015) Additional Meeting Document 11.4 Weighing of freight (shipping) containers – Legal metrology implication of an amendment to the International Maritime Organisation’s Safety Of Life At Sea (SOLAS) Convention.

- Capt. Richard Brough O.B.E, & ICHCA, I. (2016). Change and uncertainty in the container logistics supply chain. Oiml_bulletin_july_2016.Pdf.

- Cristian, A. (2011). Overweight containers, a serious threat to ships safety. Universitatii Maritime Constanta. Analele, 12(16), 11.

- Devos, P. (2013). Containers Lost at Sea. Rev. Drept Mar., 85.

- Djadjev, I., & Djadjev, I. (2017). The Carrier’s obligations over containerized cargo. The obligations of the carrier regarding the cargo: The Hague-Visby Rules, 247–327.

- Fumbuka, G. J. (1999). The causes and prevention of human error contributing to maritime accidents in Tanzania.

- Goldstein, J. (2018). Tanzania says at least 131 are dead after ferry capsizes. The New York Times, A8-L.

- Guevara, D., & Dalaklis, D. (2021). Understanding the interrelation between the Safety of Life at Sea Convention and certain IMO’s Code. TransNav: International Journal on Marine Navigation and Safety of Sea Transportation, 15.

- Hartog, F., & Ninla Elmawati Falabiba. (2023). Development of measures regarding the detection and mandatory reporting of containers lost at sea that may enhance the positioning, tracking and recovery of such containers. Angewandte Chemie International Edition, 6(11), 951–952., 5–24. Retrieved from https://www.worldshipping.org/regulatory-filings/estimate-of-containers-lost-at-sea-ccc-811

- IMO. (2014). Guidelines regarding the verified gross mass of a container carrying cargo. 44(0). Retrieved from https://www.imo.org/en/OurWork/Safety/Pages/Verification-of-the-gross-mass.aspx

- IMO. (2016). International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS), 1974. International Maritime Organisation London.

- Krilić, T. (2015). News from IMO. Transactions on Maritime Science, 4(01), 54–57.

- Rahim, G. P. (2019). Container ship accident analysis due to container stacked on deck as an attempt to improve maritime logistic system. E3S Web of Conferences, 130, 1010. EDP Sciences.

- Rahmatika, R., Putri, R. A., Sirait, D. P., & Setyawati, A. (2017). The impact of VGM (verified gross mass) implementation as SOLAS’s new regulation-case study at port of Tg. Priok. Global Research on Sustainable Transport (GROST 2017), 693–703. Atlantis Press.

- Sánchez, M. J. N. (2016). Towards a new SOLAS convention: A transformation of the ship safety regulatory framework. International Journal of Maritime Engineering, 158(A2).

- Svilen, V. (2013). Measures to enhance safety of containerized cargo transport by revising standards for cargo information and Edi Baplie and Movins messages structure. Journal of Marine Technology & Environment, 2.

- Tai, S. K. (2016). The application of the verified gross mass rules in Hong Kong. Maritime Business Review, 1(3), 225–230.

- The Merchant Shipping, T. (2016). The Merchant Shipping(Verified Gross Mass of a Container Carrying Cargo) Regulations,GN 197 2016 pdf.pdf. Retrieved from https://www.tasac.go.tz/publications/legislation

- Wasalaski, R. G. (2021). Probable causes of losses of containers from container ships. SNAME Maritime Convention, D011S001R004. SNAME.

- Youssef, E. E.-D., & Aly, H. E. (2020). Overweight containers accidents, problems and solutions. AIN Journal, (40).